by Vineet Nayar

A fellow business leader complained the other day that although he had repeatedly sought feedback, his team had never told him what they really thought about his management style. We’ve been friends for a long time, so I asked: “Do you want feedback so you can do something with it? Or are you asking only because you think that’s the right thing to do?”

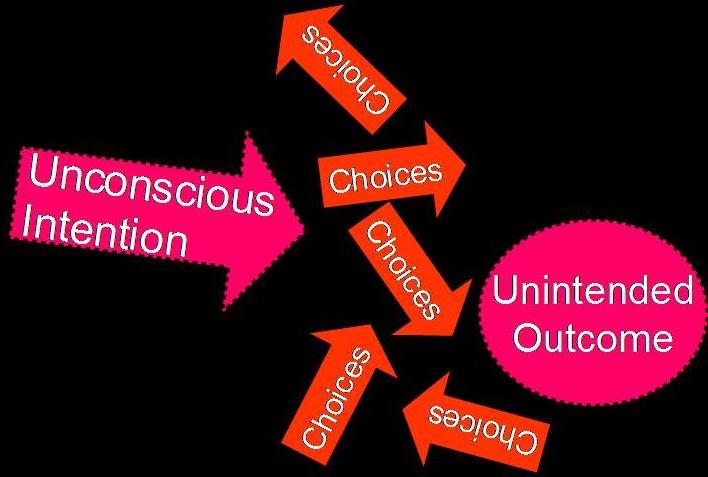

The problem, I told him, is that people can perceive your intentions right away; it has nothing to do with what you say or do. There was a long pause, and then he admitted: “Deep inside, I’m probably not ready to hear critical feedback or do anything about it. My plate is full and my team knows that.”

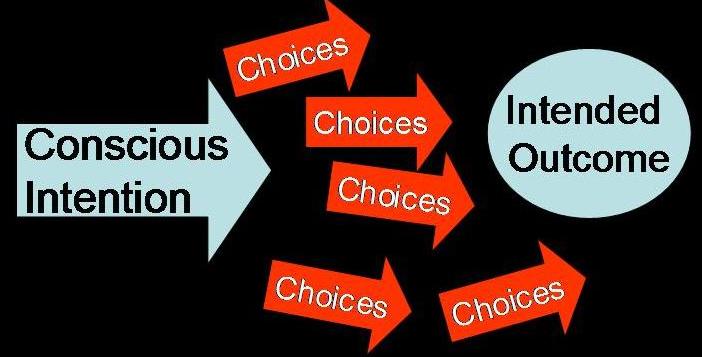

It’s critical to know your intent as a leader and to communicate it clearly.

Let me recount an amazing ritual around intentions that a friend recently described. Apparently, in some parts of Africa, when a mother conceives, she writes a song for her child and sings it to the baby in her womb all through the pregnancy. When the child is born, the village comes together to sing the same song for the child. Any time the baby cries, the mother sings that song to comfort him or her.

When the child grows a little older and the mother has to return to work in the fields, she has to leave the infant behind at home. Even though she may be out of earshot, whenever the mother feels her baby is crying or missing her, she sings that song to soothe the child. Incredible though it may seem, the child seems to sense her intent and stops crying. That’s the power of intent.

A 2007 book, The Intention Experiment, explored the science of intention, drawing on the findings of leading scientists around the world. Author Lynne McTaggart uses cutting-edge research conducted at Princeton, MIT, Stanford, and other universities and laboratories to reveal that intent is capable of profoundly affecting all aspects of our lives. In the book, William A. Tiller, a professor emeritus at Stanford University, argues: “For the last 400 years, an unstated assumption of science is that human intention cannot affect what we call physical reality. Our experimental research of the past decade shows that, for today’s world and under the right conditions, this assumption is no longer correct.”

Understanding and communicating intent is rarely given much importance in business, though. Goals and vision are shared as carefully curated documents, or through great speeches created by well-oiled communications machines. CEOs forget that if the intent of these plans isn’t aligned with the communication, people may be impressed, but deep down inside, they will not believe in those plans or act on them.

There’s little doubt that clarity of intent sheds light on the path ahead even if it isn’t clearly visible. In such scenarios the “I don’t have the right answers for you, but let’s march ahead and discover how can we get to our goals faster” articulation is more powerful than rhetoric. Articulated well, it can help draw the necessary responses from people and catalyze growth.

It’s equally important to understand the intent of competitors — an aspect often overlooked in traditional competitor analysis. Two decades ago, the late C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel referred to that in an award-winning HBR article Strategic Intent. Highlighting the journeys of Canon and Honda to dominance in the mid-1980s, they pointed out that it was intent that made the difference — not resources. Until 1970, both were relatively small companies, and since traditional competitor analysis is like shooting a snapshot of a moving car without a clue about the driver’s intent, nobody viewed them as threats. As Hamel and Prahalad point out, a snapshot by itself yields little information about “whether the driver is out for a quiet Sunday drive or warming up for the Grand Prix.”

Intent continues to be imperative for business success today. Carlos Ghosn, chairman and CEO of Nissan and Renault, is widely credited for leading a dramatic turnaround. Ghosn articulated his intent to return a near-bankrupt Nissan to profitability in 1999, and achieved that within a year. Since then, he has transformed Nissan into one of the world’s most profitable companies. I had the good fortune of talking with Ghosn recently, and found that he continues to forge ahead on the strength of bold intent. Despite the volatile world economy and the damage to the company’s plants caused by the recent earthquake in Japan, he has committed to an ambitious plan: To boost Nissan’s global market share and profits to 8% by 2016.

The lesson is clear: Any CEO or leader who wants to propel a business forward must be certain — and communicate — that the intent is unambiguous. That’s applicable at any stage of a business’s life, be it start-up, growth, transformation, reinvention, or globalization. Indeed, that’s often the first step to success. Don’t you think so?